In the United States, about two-thirds of people raised Catholic remain Catholic as adults (67%). Among those who remain Catholic, about half attend Mass at least once a month (47%). These two statistics can help shape a conceptual “map” of Catholicism in terms of defining a core and a periphery. Some people leave the faith, others remain Catholic but rarely attend Mass (i.e., periphery), and at the core are those who stay and actively participate in their faith on a regular basis.

In this post we explore who, demographically, is most likely to fall into the core, periphery, or out of the faith. To accomplish this we have aggregated respondents to the 2008 to 2014 General Social Survey (GSS). In all, this includes 2,921 responses from people raised as Catholic.

The first set of results, in the table below (click the table image to see full-size), show where people raised Catholic have ended up in terms of religious affiliation as adults. Although two-thirds remain Catholic, 16% have become Protestants or affiliated with some other Christian church. Fifteen percent have no religious affiliation and 3% are affiliated with a non-Christian faith. Below the top line of this table are these same results by different sub-groups. People in some of these sub-groups have been more likely to stay and others more likely to leave. These differences will be explored in greater detail below.

The second table (again, click the table image to see full-size), shows how frequently those who stay Catholic attend Mass. Overall, 25% of adult Catholics attends weekly (i.e., every week), 24% less than weekly, but at least once a month, 29% less than monthly, but at least once a year, and 22% less than once a year or never. Here again, some groups are more likely to attend frequently and others less so.

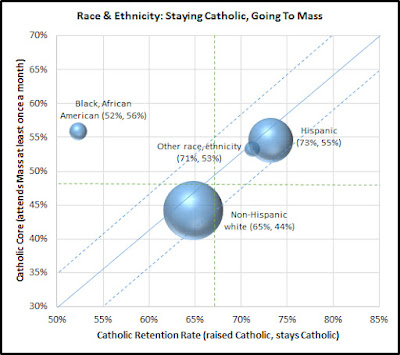

These data reveal several narratives that can be statistically plotted. Some of these stories beg rather simple inferences, whereas others are a bit more complex. Some groups have low retention and among those who stay, low frequencies of Mass attendance. Others have high retention and among those staying, high frequency of Mass attendance. These are the “linear groups” that fall between the blue lines in the scatter plots below. Outside of these lines are some outlier groups.

You can also think of the scatter plot as having four quadrants. Two of these are “outlier zones” for Catholics. In the upper left are those with low retention rates (i.e., many raised in this group leave the faith) but have high frequencies of Mass attendance among those who remain. In the lower right quadrant are groups with high retention (i.e., many in this group stay Catholic) but lower levels of regular Mass attendance among those who have stayed. In the figures that follow a third dimension is added—the size of the raised Catholic population of each sub-group. Thus, the size of a bubble represents the relative population size for those raised Catholic, the x or horizontal axis represents the percent of this population that remained Catholic and then the y or vertical axis is the share of those who stayed Catholic as adults who attends Mass at least once a month.

Generation

The life-cycle theory of religion predicts that as people become teens and then adults their religiosity falls a bit as they leave their childhood pattern of affiliation and worship. The teens and twenties are the most common age periods for those who leave their childhood faith to make that decision. Then as people age they may choose to marry and have children and as this happens many become more religious and strongly affiliated. Finally, as they age and move into their senior years, religiosity again often rises even further. In the thirties, forties, and later some who left theory faith may even return as “reverts.”

What we see in the figure below does not represent life-cycle theory well. It is the case that Pre-Vatican II Catholics, those born before 1943, are the most likely to have stayed Catholic (82% retention) and today exhibit the highest frequencies of Mass attendance (63% at least monthly). However, the other three younger Catholic generations are clustered together around the “average” Catholic. Post-Vatican II Catholics (born 1961 to 1981) have similar retention rates to Vatican II Catholics (born 1943 to 1960). However, the younger Pre-Vatican II group is slightly more likely to attend Mass at least once a month than those of the Vatican II Generation (27% compared to 21%).

Millennials (born 1981 or later) have slightly higher retention rates than the next two older generations but are much less likely to attend Mass at least once a month (39%). There is a real divide between the Pre-Vatican II Catholics and the younger generations that is unlikely to ever be eclipsed. We can’t expect that Vatican II Catholics or those who are younger to be where Pre-Vatican II Catholics are now when they reach the same ages. As more Pre-Vatican II Catholics pass away in the future (the youngest are now 73 years old), Mass attendance and retention rates for Catholics in the United States overall are likely to fall without them being in the pews.

Where life-cycle theory may be helpful is in predicting some movement for Millennials on this figure as they age. It is likely their Mass attendance frequency will rise to levels near Vatican II and Post-Vatican II Catholics. Their bubble will also grow as more of this generation enters adulthood. The current figure includes those born 1982 to 1996 (i.e., the youngest respondents in the GSS are 18).

Marital Status

In the last few years, the Church has examined family life issues. Specifically, questions have centered on divorced and remarried Catholics as well as on declining numbers celebrating the sacrament of marriage. The figure below provides some insight into how marriage and divorce may affect Catholic affiliation and practice. The figure is also reflective of the life-cycle with younger never married Catholics looking a lot like Millennials and widowed Catholics looking a lot like Pre-Vatican II Catholics.

Clearly the path outlined is not generally experienced. Many marry and eventually face a life without their spouse as a widow or widower. What this figure does speak to is the crisis of faith that likely occurs with many who divorce.

In Amoris Laetitia, Pope Francis clarified, “It is important that the divorced who have entered a new union should be made to feel part of the Church. “’They are not excommunicated’ and they should not be treated as such” (243). He adds further, “The divorced who have entered a new union, for example, can find themselves in a variety of situations, which should not be pigeonholed or fit into overly rigid classifications leaving no room for a suitable personal and pastoral discernment. One thing is a second union consolidated over time, with new children, proven fidelity, generous self giving, Christian commitment, a consciousness of its irregularity and of the great difficulty of going back without feeling in conscience that one would fall into new sins. The Church acknowledges situations ‘where, for serious reasons, such as the children’s upbringing, a man and woman cannot satisfy the obligation to separate’. There are also the cases of those who made every effort to save their first marriage and were unjustly abandoned, or of ‘those who have entered into a second union for the sake of the children’s upbringing, and are sometimes subjectively certain in conscience that their previous and irreparably broken marriage had never been valid’” (298).

Pope Francis calls for a consideration of these circumstances in noting, “it is understandable that neither the Synod nor this Exhortation could be expected to provide a new set of general rules, canonical in nature and applicable to all cases. What is possible is simply a renewed encouragement to undertake a responsible personal and pastoral discernment of particular cases” (300). How Amoris Laetitia is applied in practice may, in the future, alter some of the patterns that are evident in the figure above.

Education

So far, the figures have shown distributions that generally lie along the predicted pattern of lower retention and lower Mass attendance and higher retention and higher Mass attendance that moves from the bottom left to the top right of the scatter plots. The story of education takes a different path. As shown below, as people raised Catholic attain higher levels of education, retention likely drops and among those who remain Catholic, Mass attendance is likely quite high, relatively speaking. Retention is highest among those with a high school diploma or less with more than seven in ten staying Catholic. Yet among those who stay with this level of education, only about four or five in ten attends Mass at least once a month.

Among those who attend some college and those who obtain college degrees retention falls to less than seven in ten but among those who remain Catholic in these higher education groups, majorities attend Mass at least once a month.

CARA is currently conducting research on why some young Catholics leave the faith. One of the most surprising themes that is coming to the surface in this research is the notion among some that the Catholic faith is incompatible with science and that some have chosen science to actually be their faith. In a popular culture that increasingly sees non-belief or atheism as “smart,” some may be losing their faith and would only return if they had, as one respondent put it, “replicable, peer reviewed, conclusive proof that a deity exists and I'm guaranteed a happy after life.” That is a crisis of faith. Not the Catholic faith but just the notion of faith in general. In a culture where atheism and smart are synonymous, faith pairs with what?

Does going to college lead some to a loss of faith? Perhaps. Or is it the nature of the 21st century curriculum? I learned evolution in a Catholic school from a religious sister. A war between Catholicism and science has never seemed real to me. But most young Americans being raised Catholic today (or the recent past) are never in Catholic schools or colleges. Most aren’t even in parish-based religious education. The data seem to indicate that among those with some college or a degree who stay Catholic are more active in the faith than those with less education. Is there any correlation between these individuals ever being enrolled formally in a Catholic educational institution or program? Perhaps... Stay tuned for more on this topic as CARA is also currently conducting a major study about religion, science, and education.

Birthplace and Citizenship

Nearly half of foreign-born residents in the United States are Catholic (45%). Most are coming from countries where Catholicism is shared by large majorities of the population. When they come to the United States they encounter a very different religious culture with many new options. They may also be in a part of the country where the Church does not have many parishes or other institutions.

As shown in the figure below, foreign-born residents who are raised Catholic are more likely than those born in the United States to stay Catholic as adults and to attend Mass at least once a month. However, there is an important difference. Typically an eligible non-citizen would need to wait a minimum of three to five years to go through naturalization. Once citizenship is attained, the data indicate that retention drops slightly but among those who remain Catholic, Mass attendance is likely to rise a bit. There are many potential explanations. One possibility is that some of the foreign-born who are undocumented non-citizens may be less likely or even able to attend Mass. For example, foreign-born migrant farm workers often are visited by Catholic ministers and clergy where they work and live because it may be difficult for them to travel to the closest parish. They may also be hesitant or cautious in joining or engaging with parish communities that are unfamiliar to them.

During the period before they might be able to seek citizenship they may also become familiar with other faiths. They may be intrigued by Protestant church that is advertising an Our Lady of Guadalupe celebration. As has been frequently observed, the bigger shift in affiliation and worship may come with the children and grandchildren of immigrants. Here, retention and frequency of Mass attendance may start to look a lot like it does for all U.S. born citizens regardless of ancestry or nationality.

Race and Ethnicity

There is one noticeable outlier in terms of race and ethnicity. Black Catholics are among the most likely to leave the faith, but among those who stay, worship levels are comparatively quite high. Only 52% of black or African Americans raised Catholic remain Catholic as adults. Yet, among those who remain Catholic, a majority attend Mass at least once a month. Only about 3% to 4% of Catholics self-identify their race as black or African American. Few black or African American residents self-identify as Catholic as well—about 6% or 7%.

Why do so many Black Catholics leave? My own hunch is that it may have something to do with peers and partners. Many black Catholics may have Protestant peers and significant others. From childhood into the early twenties they may be more likely than other Catholics to be introduced to other Christian denominations and some may choose to leave the faith of their parents for the faith of their peers or partners. There may also be something related to gender that is important. In research CARA is doing in culturally diverse parishes we’ve found that 72% percent of black Catholics born in the United States, surveyed in the pews during Mass, are female and 28% are male. This is the biggest gender gap of any race and ethnicity group.

Note that non-Hispanic white adults have relatively low retention rates and among those who stay, frequency of Mass attendance is comparatively the low. By comparison, Hispanic or Latino as well as those of other some other race or ethnicity (primarily Asians, measuring approximately 4 percent of all adult Catholics) have higher retention and more frequent Mass attendance than non-Hispanic white Catholics.

Sexual Orientation

The final comparison follows the linear path. Only 56% of those raised Catholic who self-identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual remain Catholic as adults. Among those who stay, Catholic only about a third attend Mass at least once a month (35%). Heterosexual Catholics are at the center of the distribution with average retention rates and frequencies of Mass attendance.

As seen in the tables above, no other sub-group is more likely to have no religious affiliation than those raised Catholic who self-identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual (28%). They are also among the least likely to switch to a Protestant denomination (11%). While a majority remain Catholic, those who do are infrequent Mass attenders, relatively speaking. Is this an issue of not feeling welcome or included in parish life?

The Catechism instructs that gay, lesbian, and bisexual individuals “must be accepted with respect, compassion, and sensitivity. Every sign of unjust discrimination in their regard should be avoided” (Canon 2358). At the same time, in Amoris Laetitia, Pope Francis states that “there are absolutely no grounds for considering homosexual unions to be in any way similar or even remotely analogous to God’s plan for marriage and family” (251). Yet, he also reiterates the aforementioned teachings of the Catechism and asks pastors to “avoid judgements that do not take into account the complexity of various situations” (79). He adds that “It is a matter of reaching out to everyone, of needing to help each person find his or her proper way of participating in the ecclesial community. ... No one can be condemned forever because that is not the logic of the Gospel! Here I am not speaking only of the divorced and remarried, but of everyone, in whatever situation they find themselves” (297).

Conclusions and Implications

Since 1996, CARA has been conducting in-pew surveys of parishioners at Catholic parishes across the United States. Today, we have done this in nearly 1,000 parishes. About nine in ten surveyed say their overall satisfaction with their parish is “good” or “excellent.” In part, this is because increasingly Catholics are looking for and finding a parish they like best rather than attending their territorial parish. We ask parishioners what attracted them to the parish they are in. Overall, 86% say they were attracted by their parish’s “open and welcoming spirit” and the same percentage say by the “sense of belonging” they feel in their parish. The only other factors attracting them a bit more are the quality of the liturgy (89%) the quality of the preaching (87%). There are many out there selling a secret formula for parish renewal. At CARA it’s always been simple: a good pastor and ministry staff along with an overwhelming sense of welcome. If you build that it is very likely a community will form and grow—from the core, periphery, and perhaps even further out into orbit.

Demography is not destiny and there are undoubtedly many anecdotes that do not fit the stories that emerge from the data described above. However, probabilities are useful. The patterns in the GSS data reveal which groups the Church in the United States is retaining and engaging most. The table below shows how different (and similar) these core, periphery, and formerly Catholic parishes are in the United States today: