Social science is not just about surveys, trend data, or focus groups. Some of my favorite types of research involve content and historical analysis. The study of art, for example, can provide some amazing insight that is not visible on a spreadsheet. Norman Rockwell’s “Sunday Morning,” as shown below (click to enlarge), has always caught my eye as an interesting piece because it brings to life some of the survey results we have been seeing for many years and it did it on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post all the way back in May of 1959 (for more see: “Sunday Morning Slackers” from the Post).

Rockwell illustrated this piece five years after appearing in the national print ad shown below, which reads, “Light their life with faith. Bring them to worship this week.” This advertisement was sponsored by Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish lay people in an effort to encourage weekly religious service attendance—especially among parents with their children. This should be the first sign of something amiss with our recollections of this time…

According to his biographer (Norman Rockwell: A Life, by Laura Claridge, Random House, New York, 2001), Rockwell lived a life much more like his cover illustration than the text of the ad campaign. He was said to rarely make it to church on Sunday during his first marriage (to a Catholic woman he later divorced) or during his second marriage (to a woman of his own Episcopalian affiliation). Rockwell did have his children baptized from the second marriage but was not a regular at church services otherwise.

In itself this may come as a shock to those who view Rockwell as the visual soul of conservative, small town, religious America. As “Sunday Morning” indicates Rockwell was not shy about pointing out the realities of American religious life even in the 1950s. Take special notice of the father’s unusual morning-bed hair-style and the color of his robe. When one realizes from his biographer that Rockwell may have spent many similar Sundays in his pajamas it is more difficult to typecast the illustrator into some of his other more famous and pious illustrations regarding religion.

It is likely that the family in the illustration is Protestant. Thus, it is not the case that Rockwell was making any comment about Catholicism in this work. But the fact that it made it on to the cover of America’s magazine of record at the time indicates that it resonated with the culture of this period. This issue of the Post was published at a time when weekly Catholic Mass attendance was peaking, as measured in Gallup telephone surveys (74% in 1958 and 72% in 1959). In 2008, Gallup surveys estimated Catholic Mass attendance in any given week had fallen to 42%. Don’t giggle. I know you don’t believe that 42% of Catholics nationally attend Mass in any given week and you’re right. But why do we believe 74% did in 1958?

I am sure there will be some reading this who says, “I remember, I was there.” But what we did see in the 1950s is not important. It is what we did not see… the people who were not in the pews. You can only get an attendance percentage by dividing the Mass attendance count (numerator) by the number of self-identified Catholics in the parish boundaries that could have attended (denominator). All of this is unlikely to be found in your memories! (Note: even Robert Putnam who notorious for highlighting the declining trend lines from the 1950s says the following in American Grace: “research on the accuracy of reporting church attendance… suggests that we should take these self-reports with a grain of salt,” pg. 571).

A piece of art is one thing. Perhaps more can be said by taking a second look at a researcher who was in many Catholic parishes studying Mass attendance in the 1950s. Joseph H. Fichter, S.J., (granduncle to current CARA research associate Fr. Stephen Fichter) famously studied parish life by going door to door and taking censuses, making Mass attendance head counts, observing parish life, and documenting everything possible both qualitatively and quantitatively.

In his 1954 study, Social Relations in the Urban Parish (University of Chicago Press), Fichter estimates Mass attendance levels based on the number of individuals registered with the parish. But he also provides the counts for what he calls “dormant Catholics” from his census within parish boundaries. These are people who self-identify their religion as Catholic but who do not attend Mass. Thirty-eight percent of the Catholics within the parish boundaries he studied in this book were dormant. Thus, at the outset we know that typical weekly attendance by the measure of this study could have been no more than 62%. But what about among the “active” Catholics? About 79% of the non-dormant Catholics attended Mass on a typical weekend. So overall, the total percentage of self-identifying Catholics attending Mass in this study was estimated to be about 49%.

This is almost exactly what we get in the early 1950s if we “correct” the Gallup trend numbers down for “over-reports” in each year by about 12 percentage points (Why 12 percentage points? See “The Nuances of Accurately Measuring Mass Attendance” and more recent research cited below). The figure below shows this correction for the entire Gallup series.

Attendance over-reports occur as people being interviewed over the phone respond to their interviewer with answers about their behavior that they believe to fit socially desirable expectations. So typically the respondent has just told the interviewer their religion and then they are asked how often they attend services. Many respond in a way that they believe is socially acceptable—even if it does not fit their actual pattern of attendance.

We have some early evidence of this in the Americans’ Use of Time Study, 1965-1966. Here, 57% of Americans when asked directly about their church attendance reported that they had attended in the last week. However, only 39% of these respondents actually indicated attending religious services when recording their time use hour by hour in diaries (i.e., an indirect measurement). For more on this see Philip Brenner’s excellent recent article “Identity Importance and the Overreporting of Religious Service Attendance” in the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion (March, 2011; pgs 103-115). Brenner not only estimates this phenomenon in the United States but in Europe as well, where this issue is less of a problem. These estimates are in “Exceptional Behavior or Exceptional Identity?” in Public Opinion Quarterly (Spring, 2011; pgs. 19-41). For example, in Italy (2003) time diaries estimate church attendance to be 25% weekly but surveys measure this at 30%. In Spain (2003) attendance is estimated at 16% in time diaries compared to 19% in surveys. In Ireland (2005) these numbers respectively are 42% (time diary) and 46% (survey-based). Here, Brenner also shows that from 1975 through 2008 the average annual over-report in U.S. religious attendance is very stable and much higher than in Europe, at an average of 13.4 percentage points.

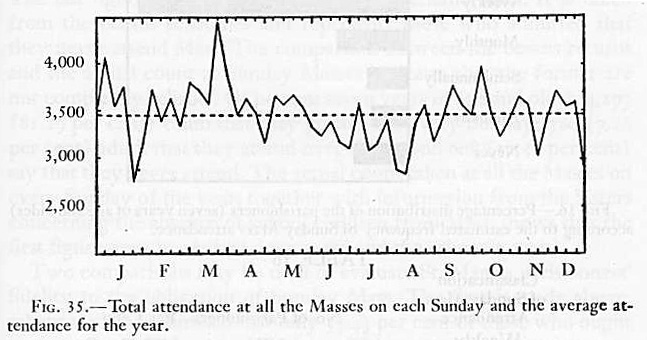

In another of Father Fichter's 1950s studies, Southern Parish: The Dynamics of a City Church (Volume I, University of Chicago Press, 1951), he showed that there was also considerable variation in Mass attendance week to week (see figure below). This again is quite similar to some indirect measurements made now. Just as today, Lent brought more Catholics to Mass than during other periods of the year.

Joseph H. Fichter; Southern Parish: The Dynamics of a City Church; Volume I, University of Chicago Press, 1951, pg. 151.

Father Fichter’s observations also indicate that some of the Mass attendance of the 1950s was not as “active” as we might remember it. Here is a passage that likely still resonates with your observations of parish life today:

“A measure of the parishioners’ devotion to the Mass and of their fulfillment of this obligation is seen in the numbers who arrive late and who leave early. By actual count it was noted that, at all Sunday Masses, 8.37 per cent of the congregation arrived after Mass had started and that 6.35 per cent left before it was completed. … Although we have no accurate count, we have noticed that many of these persons are duplicated in both categories. In other words, those who come late also tend to leave early. … The younger males constitute the majority of those who omit part of the Mass, while older females make up the majority who arrive in church well in advance of Mass” (1951, pg. 138).

“By actual count, 35.08 per cent of the congregation read the missal all during Mass, while another 22.08 per cent read some sort of prayer-book while following the priest’s reading of the Gospel. … The remaining persons simply stare off into space, although several men in the last pews sometimes read a copy of Our Sunday Visitor during Mass” (1951, pg. 138).

Over a year of Masses, on average, attenders were much more often female (about 7 in 10 or more) than male—a composition that can only result from some men, perhaps like the man in the Rockwell illustration above, staying home.

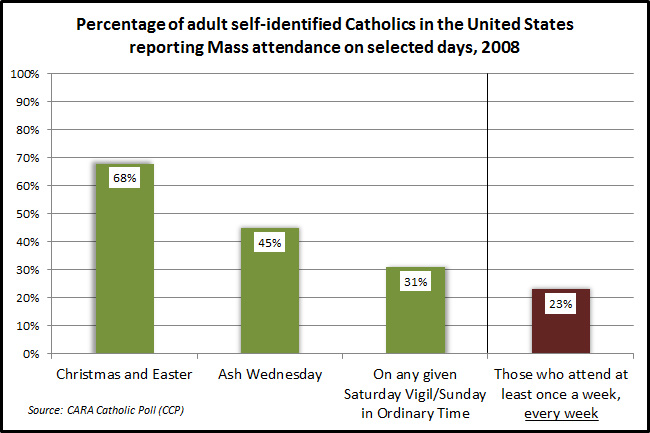

Today, CARA’s national surveys use a methodology that minimizes social desirability pressure on respondents to get the most accurate measurements of Mass attendance possible. Many cite our weekly Mass attendance figure in the low 20 percent range. Some also then cite Gallup’s figure from the 1950s and attempt to argue that Mass attendance has fallen from nearly 80% to just above 20%. This is misleading and inaccurate. First, as shown above, the Gallup numbers for the 1950s are inflated by over-reports just as they are in the 1970s or now. Second, CARA and most other survey-based estimates of Mass attendance measure general frequencies of attendance such as “every week” or “at least once a month.” Gallup’s church attendance question measures whether a respondent has attended in the last 7 days. Depending on the week in which this question is asked, one will get very different results. Thus, the best use of the Gallup data is in taking the average for the year in response to this question.

Currently, CARA surveys indicate that 23% of self-identified adult Catholics attend Mass every week. Yet, in any given average week, 31% of Catholics are attending (almost identical the “adjusted” 30% estimate from the Gallup trend). Note there is considerable local variation in Mass attendance levels with higher levels in the Midwest and lower in coastal urban areas). During Lent and Advent, Mass attendance increases into the mid-40 percent-range and on Christmas and Easter, an estimated 68% of Catholics attend.

Thus, if one is seeking to make a comparison of Mass attendance in the 1950s to now, the drop is not 80% to 20%. Instead it is from a peak of 62% in 1958 to about 31% now. This is still a remarkable decline. It means that the Mass attendance you see at Christmas and Easter is a lot like the attendance you might have seen in a typical week in the late-1950s. Yet, even then, as now, there is a significant number of Catholics like the father in Rockwell’s “Sunday Morning” who choose to do something else.

The slope of the Gallup declining trend is accurate. It’s the levels that are off. If you are going to use the Gallup data from the 1950s and make comparisons to CARA data in the 2000s and beyond you’ll need to adjust the Gallup trend (and our collective memory of the 1950s) down to reach reality. And this is of course is not just an artistic endeavor. As I have argued here I believe it to be statistically valid.