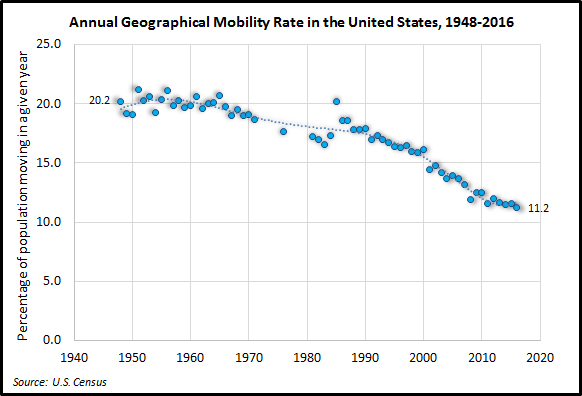

Contrary to “conventional wisdom” Americans are moving less now than they have in the past. The “mover rate” in 2016 was 11.2% (i.e., the percentage of Americans moving in a given year).

For the Catholic Church, it is not so important how many people move, but where they end up going. According to the Census (ACS 1-year estimates from person-level reporting), in 2016, the top destinations for people “moving in” from out of state were within the following diocesan boundaries: Seattle (WA), Atlanta (GA), Phoenix (AZ), Los Angeles (CA), Galveston-Houston (TX), Raleigh (NC), Richmond (VA), Orlando (FL), and Charlotte (NC). These dioceses are all either in the South or West. One of the central themes of CARA’s recent book, Catholic Parishes of the 21st Century (Oxford University Press, 2017) is the geographical shift in the Catholic population away from the Midwest and Northeast. This transformation continues.

The Census data does not include any information about religion. However, if one assumes that movers from a particular area have a similar religious makeup to those who do not move from that area, we can create estimates for the likely share of Catholics among movers. CARA utilized religious affiliation estimates from Pew (1, 2), PRRI, and the Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae to estimate movers’ religions based on the profiles of the communities they moved from.

The table below shows the dioceses with the largest estimated numbers of new Catholics “moving in” from out of state during 2016. This ranges from more than 30,000 new Catholic residents in the Archdiocese of Washington to nearly 70,000 in the Archdiocese of Miami. Each diocese has some variations in where people are moving from. For example, in the Archdiocese of Miami, a majority are coming from outside the United States, whereas in Archdiocese of Washington they are coming from nearby states and large states elsewhere in the country. Also note that these data do not account for the numbers of people moving out of a diocese (or moving from within state), the number of new births, and the number of deaths. Thus, these are not estimates of overall Catholic population growth. Regardless, each of the dioceses in the table below have more than 30,000 new Catholic residents from out of state who may need to connect with a parishes and schools as well as other institutions like charities and hospitals.

The dioceses that are shaded in the darkest green on the map below (click to show full size) have the largest numbers of new Catholics moving in. These are regions where parishes need to reconnect Catholics to the life of the Church in their new home.

It is perhaps no surprise that dioceses with larger populations have more people moving in. People often move for jobs, retirement, or to be near family. It’s also not all that surprising that Catholics may be going to places where there are already many Catholics. What about the dioceses where people move in and there are not many Catholics, relatively speaking, to welcome them?

The number of parish-affiliated Catholics in dioceses is recorded in The Official Catholic Directory each year. These are Catholics known to the Church. In every diocese there are additional people who self-identify as Catholic but who do not attend Mass regularly or register with a parish. The estimates for Catholics moving in includes some who will become parish-affiliated in their new location and some who will not. The table below shows dioceses where Catholics are moving in and where there are not many parish-affiliated Catholics already present to welcome them. For example, in the The Archdiocese of Mobile in Alabama there are only about three parish-affiliated Catholics for every new self-identified Catholics moving in during 2016. The dioceses with an asterisk (*) appear in this table as well as the previous table measuring the dioceses with the largest numbers of Catholics moving in. These dioceses are perhaps most in need of developing welcoming committees.

From year to year it may seem that few dioceses have big Catholic population losses or growth. Yet, what is missed in these aggregate totals is the “invisible churn” of people moving in and out as well as the changes that come with new births and some passing away. Although it may seem like there are just as many Catholics in dioceses that were there in the year previous, these data for people moving in show that significant portions of that Catholic population in many dioceses may need help and time settling in.

Regardless of overall growth, all the dioceses with many new Catholics moving in face challenges. Then again having many new faces is just the kind of dilemma that most diocesan, parish, and school leaders are probably happy to have.

Image courtesy of Nicolas Huk.